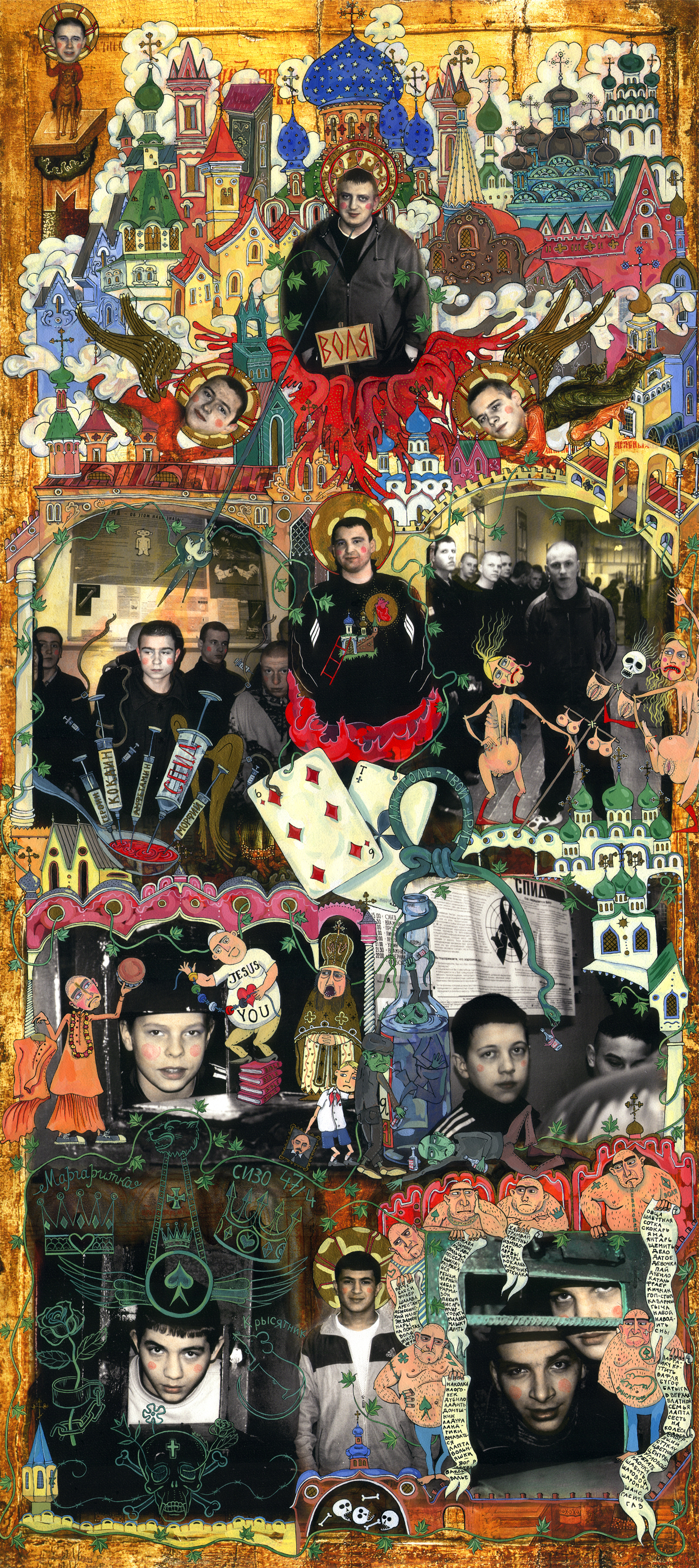

The artwork of Yana Payusova can not be viewed simply on a visceral level without being asked to see the social commentary and to decipher numerous embedded symbolic elements. This particular body of work was inspired by Payusova’s experience of studying and listening to personal stories of incarcerated teenagers (14-21 year-old boys) at Lebedeva and Kolpino prisons in St. Petersburg. Many of them became the victims of the economic chaos that followed the breakup of the Soviet Union. Searching for an answer to a profound question of “What is a society’s role in labeling these young men as criminals, convicts, felons and sinners?” is the philosophical underpinning of Payusova’s work.

In order to answer this question, she constructs a visual language where the traditional black and white photographic imagery is mixed with the iconographic and symbolic elements of Russian Christian Orthodox culture from the twelfth to fifteenth centuries. Combining the realistic quality of digital imagery (young mens’ faces) with a visionary quality of painting (the overall imagery) allows the intricate and quintessentially Russian elements to assume an avant-garde design. She strives to unite the traditional and nonconformist to transform the one-dimensional meaning into a purely modern composition. Every painting becomes a poetic invitation into the subjects’ life, thoughts, pain and sufferings.

Payusova’s work, with its strong imagery, the play of consciousness and her unique juxtaposition of images, immediately brings the viewer into the world of these young men. Through the codified symbols of the Russian society, Russian Orthodox Church and the prison rhetoric, Payusova combines this heavy symbology with direct representation of the young mens’ faces to remind us of a complexity of life. It is this juxtaposition between their personal narrative and society’s reaction to them that allows one to search for an answer to this fundamental question of society’s judgments of saints, sinners and martyrs. In her own words: “What we fail to see are the reasons, the incentives for those kids to commit the crimes.”

Narrating the personal story of these teenagers, Payusova manages to deliver this complex sociological notion in an intimate and personal style. In the end, she presents us with the world that is not only filled with pain and loneliness, but also with poetry and lyricism. It is this melding of the symbolism and reality that carry with it greater power and deeper meaning. In her own words: “To shock or to insult the viewer is not my intention. I want them to consider what is more important - an icon or: a human life”.

-Angelica Semmelbauer, Mimi Ferzt Gallery

This body of work was inspired by my experience volunteering at prisons in St. Petersburg, Russia. I was primarily working with incarcerated teenagers (14-21 year old boys), who are victims of the economic chaos that followed the breakup of the Soviet Union. These kids either grew up on the streets or came from highly dysfunctional families. I spent a year getting to know these people, their stories, and their personal histories. In retrospect, I started thinking of how we, as society, label these kids: criminals, convicts, crooks, felons, villains, sinners. What we often fail to see are the reasons, the incentives for these kids to commit crime.

I am exploring eternal concepts of saintliness, sins, holiness, and martyrdom. For this purpose, I have constructed a visual language where the traditional black and white photographic imagery is mixed with the painted iconographic and symbolic elements of Russian Christian Orthodox culture. By merging and mixing these referents, my intention is to call into question how we define and judge saints and sinners and what factors contribute to the creation of both.

As the project evolved, I began to see the prison community as mirroring and mimicking the organization of general Russian society. Further along, I also began noticing similarities between prison and church cultures. Both are structured by rigid hierarchies and employ secret languages known only to a privileged few. Russian Orthodox Church uses an old form of Slavic Russian in its services and writings. The prisoners also use a secret language, one that has been passed verbally. Similar to the American hip-hop vernacular, Russia’s “blatnaya fenya” has infiltrated the popular culture; it is considered “cool” to speak the lingo of the inmates from the “zone.”

Both church and prison cultures use complicated visual language, codified through use of certain symbols and the positioning on the pictorial plane. Orthodox iconography was not intended to be confusing or elitist; rather, the visual language had lost its original clarity and simplicity as the centuries passed. Prisoners invented their own visual language through tattooing the body. In this case, the pictorial plane becomes the body.

Visually entangling the histories and parallels of church and prison cultures, I wish to challenge the branding of present-day sinners.

-Yana Payusova